Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, www.metmuseum.org

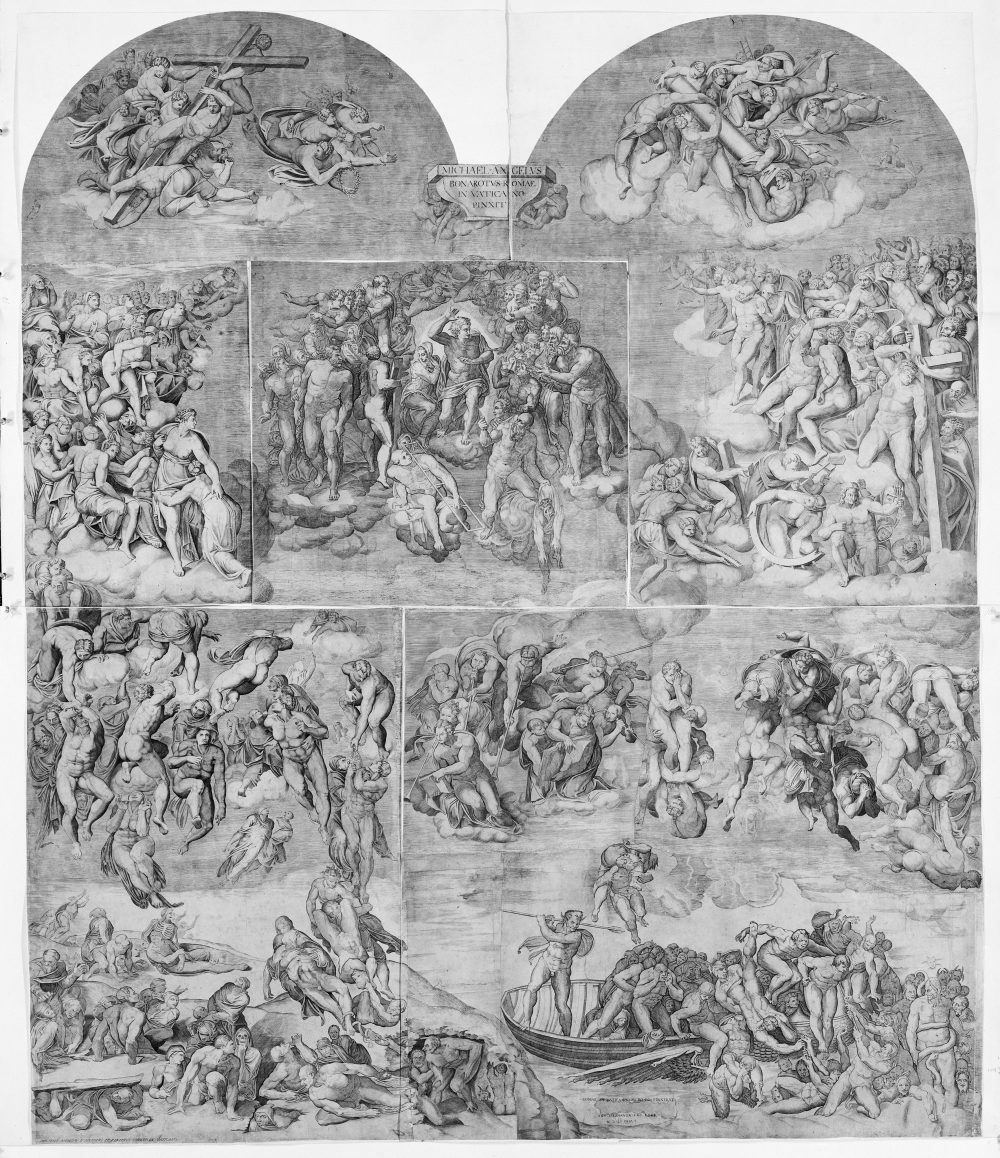

Although the characters have already spoken several times about Michelangelo’s “Last Judgement” (1535-1541), the main criticism now follows. (Gilio 2019, fig 19) Interesting about this passage is the indication that the characters, and consequently the author, have probably never seen the fresco in person, but must refer to an engraving.

First of all, M. Francesco praises Michelangelo and his work beyond all measure and puts him on a par with ancient artists such as Apelles, Zeuxis and Praxiteles. The “Last Judgement” is a model and reference for all contemporary young artists who want to learn the art of painting. Statues should be erected in his honour in every country, since he restored the decorum of art with his work, surpassing even the ancient masters. Although M. Silvio agrees with him, he gives the word to M. Ruggiero, since he alone, as a doctor of the sacred writings, can pass judgement on whether Michelangelo has depicted the truth of history or not.

His verdict is less positive. For Messer Ruggiero, the artist had tried more to satisfy art and to portray its glory rather than the truth of the subject depicted. Thus begins the critique of Michelangelo’s “Last Judgement”, in which the characters devote themselves to individual figures and themes.

‘M. Silvio said: ‘Now it remains to plow the greatest and deepest ocean that there is, in order to complete our discussion of the historical painter’.

‘What is that?’ responded M. Francesco.

M. Silvio replied: ‘The discussion of the Last Judgement that Michelangelo painted in the Sistine Chapel, in which he has shown what the art (of painting) is capable of. He has done this in such a way that it amazes not only those who see it but everyone in the world who hears about it’.

M. Troilo said: ‘We should have some representation of it in front of us in order to discuss it properly’.

‘That is well’ replied M. Francesco. ‘I will straightaway have a print of it brought, which I have hung up on the wall of the room below the dovecote’.

And having said this he ordered a servant to bring it to him; he immediately went and brought it to M. Francesco, who, as soon as he received it, opened it because it was folded, saying: ‘Here my Lords is the composition of the brilliant Michelangelo; the place where I think all modern painters learn what and how great the art of painting is. For in it he has achieved such excellence that he deserves to have statues erected to him in every country and even in every city, In order that those who came after may hold him in the same veneration as we hold Apelles, Zeuxis, and other famous painters, and in sculptures Praxiteles, Phidias, and those others whose fame in the world will never die. For truly he deserves eternal praise for having restored the art to its decorum [decoro], and for having elevated it and rendered it illustrious, thus elevating the ancients and surpassing the moderns’.

M. Silvio said: ‘You have put it well, but however much one says, it deserves more. And because the subject is an ecclesiastical and theological one, the person to talk about it is M. Ruggiero. He is a canon and a doctor who has carefully studied holy scripture’.

M. Vincenzo replied: ‘That’s well said, so M. Ruggiero, without making any excuses, perform your part and inquire into whether Michelangelo has in this case followed opinion of the holy doctors and observed the truth of the history’.

M. Ruggiero replied: ‘You have placed too great a burden on me, yet I will obey your instructions. If we consider its purity as history, I think we will find there more personal invention [capricci] than truth. For Michelangelo has prefer to satisfy the art (of painting) in order to demonstrate what and how great it is, rather than the truth of the subject matter. He has behaved like a person in love who, to please his beloved, has regarded everything as permissible. And I think the reason for this is that finding himself with such a large space and so many figures with which to show every possible movement and pose that the human body can gracefully adopt, he did not wish to lose the opportunity of leaving to posterity a record of his extraordinary mind. And it is a wonderful thing that no single figure in this portrayal does the same as another, and non resembles another. In order to achieve this he set aside devotion, reverence, historical truth, and the honor due to such a very important and great mystery, which no one should think about, let alone see, without experiencing the greatest terror’.

M. Pulidoro replied: ‘I don’t think there is a painter, even the most stupid, who does not know that Michelangelo wishes to satisfy the art (of painting) rather than the historical truth. What he has failed to do, not from ignorance but from the desire to show posterity the excellence of his mind [ingegno] and the excellence of the artistic skill [arte] that he possesses’.

M.Silvio said: ‘So now, in terms we can understand, start pointing out to us in turn the places where he has satisfied the art rather than the truth, telling us about the order of events, which I have never fully understood’.

M. Ruggiero replied: ‘I am happy to do it; but be on your guard to recognize different elements – the true, the fictional, and the fabulous – that are to be seen there. I say then that the historic painter is in all respects like a writer: whatever the one describes with his pen, the other must describe with his brush. However, both must faithfully and fully display the truth, not allowing into their works anything concealed, contaminated, or imperfect. And it appears to me that the artists who came before I Michelangelo paid more attention to truth and devotion than to ostentation’.”

“Soggionse M. Silvio: ‘Resta ora, per finir il ragionamento del pittore istorico, a solcare il maggior e più profondo pelago che vi sia’.

‘Qual è?’, disse M. Francesco.

Rispose M. Silvio: ‘l ragionare del Giudizio che Michelagnolo ha fatto ne la Cappella, nel quale ha dimostrato ciò che può e sa far l’arte; di maniera che fa stupire non solo chi lo mira, ma chi lo sente e tutto il mondo’.

Disse M. Troilo: ‘Bisognerebbe averne qualche disegno Innanzi, per poteri o ben considerare’.

‘Benissimo dite’, rispose M. Francesco, ‘et io ne farò venire or ora un disegno in stampa, che l’ho attaccato al muro ne la camera sotto la colombara’.

E così detto, commandò ad un servitore che lo portasse; il quale tosto andò e portòlo a M. Francesco, il quale, come l’ebbe in mano, l’aperse, che era piegato, dicendo: ‘Eccovi, Signori, il modello de l’ingenioso Michelagnolo, dove penso che tutti i pittori moderni imparino a sapere quale e quanta sia l’arte de la pittura; per la quale egli n’è venuto in tanta eccellenza, che meritarebbe che ogni provinzia, anzi ogni città, gli dedicasse la statua, acciò i posteri l’avessero in quella venerazione che noi abbiamo Apelle, Zeusi e gli altri famosi, e ne la scultura Prasitele, Fidia e gli altri la cui fama mai mancherà al mondo. Perché veramente è tale che merita eterna lode per aver restituita l’arte al suo decoro, e per averla rilevata et illustrata di maniera, c’ha pareggiato gli antichi e superato i moderni’.

Disse M. Silvio: ‘Dite benissimo, ché tanto non si potria dire, che più non meritasse. E perché questa è materia ecclesiastica e teologica, M. Ruggiero, come canonico e dottore a cui appartengono le Sacre Scritture, le quali egli diligentemente studia, ne le potrà dechiarare’.

‘Voi dite bene, rispose M. Vincenso; però, M. Ruggiero, senza fare altre scuse, dechiarate omai la vostra parte, e vedete un poco se Michelagnolo ha in questo caso sequitata l’opinione de’ sacri Dottori et osservata la verità de l’istoria’.

Rispose M. Ruggiero: ‘Troppo gran carico m’avete posto addosso; pur io ubidirò a quanto mi comandate. Ma se vogliamo considerare la purità de l’istoria, penso che su più capricci che verità vi troveremo: perché egli più s’è voluto compiacere de l’arte, per mostrar quale e quanta sia, che de la verità del soggetto, et ha fatto come l’innamorato, il quale, per sodisfare a la sua favorita, ogni cosa stima lecita e bella; e ciò penso che da altro proceduto non sia, che, vedendosi innanzi sì largo campo da mostrare, in tanta moltitudine di figure, tutto quello che vagamente può fare un corpo umano per via di sforzi e d’altri posamenti, non ha voluto perdere l’occasione di non lasciare a’posteri memoria del suo mirabile ingegno. E questa è la maraviglia: che nissuna fi gura, che in questo ritratto vedete, fa quello che fa l’altra, e niuna rassimiglia a l’altra; e per questo fare ha messa da banda la devozione, la riverenza, la verità istorica e l’onore che si deve a questo importantissimo e gran mistero, che nissuno lo doverebbe pensare, non che vedere, senza grandissimo spavento’.

Rispose M. Pulidoro: ‘Non penso che sia niuno, quanto si voglia goffo pittore, che non sappia o non pensi che Michelagnolo più tosto compiacer voluto si sia de l’arte, che de la verità istorica, e quello che egli non ha fatto non sia da ignoranza proceduto, ma dal voler mostrare ai posteri l’eccellenza del suo ingegno e la eccellenza de l’arte che è in lui’.

Disse M. Silvio: ‘Or dunque, per capacità nostra, cominciate a mostrarci di mano in mano i luoghi, ne’ quali egli più de l’arte che del vero s’è compiaciuto, dechiarando l’ordine de l’istoria, che io non ho mai più intesa’. ‘So’contento, rispose M. Ruggiero; ‘però state avertiti, acciò possiate conoscere le parti vere, finte e favolose, che su vi sono. Dico dunque che ‘l pittore istorico essendo in ogni cosa simile a lo scrittore, quello che l’uno mostra con la penna, l’altro mostrar doverebbe col pennello: l’uno e l’altro però deve essere fedele et intiero demostratore del vero, non intromettendo ne l’opera cosa mascherata, adulterata et imperfetta. E mi pare che i pittori che furono avanti Michelagnolo più a la verità et a la devozione attendessero, che a la pompa’.”

Gilio 2018, 156-160, n. 202-206, fig. 19-22